Every year the national network of Black-led bike clubs hosts a series of tribute rides across the country in honor of world-champion cyclist Marshall “Major” Taylor’s birthday. On November 26, We will ride in Minnesota and our partner clubs around the country will join in the commemorative recognition of Taylor’s incredible story and lifetime achievements.

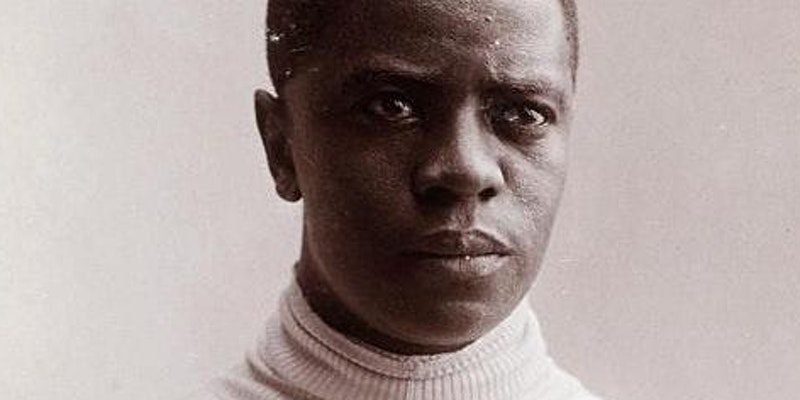

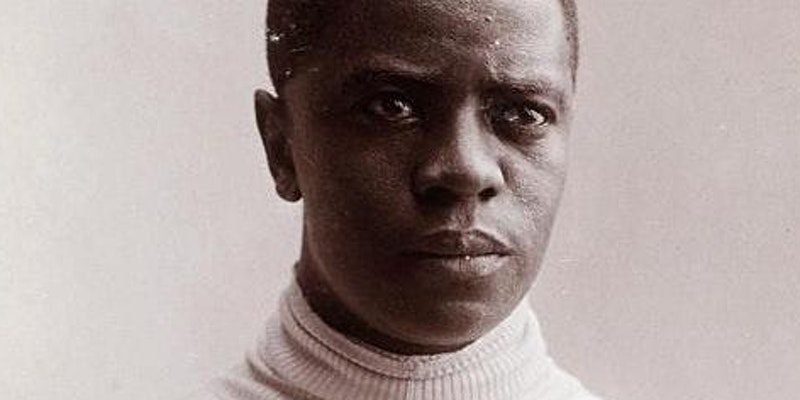

Marshall “Major” Taylor is a Black athlete and cycling legend who was one of the greatest bicyclists of his era, setting numerous world records and winning a World Championship and multiple national championships–all while battling racism throughout his career from the late 1800s to early 1900s. He was an international superstar whose superhuman exploits were as well-known in his era as LeBron James or Michael Jordan are today.

As the bicycle industry and cycling community turn their attention to the Black Lives Matter movement and the racial injustices Black people continue to face more than 150 years after the Emancipation Proclamation, the story of Marshall “Major” Taylor, “the fastest man in America,” is more relevant now than ever.

Born in 1878, Taylor was a powerful sprinter who established numerous world records in races covering distances from a quarter-mile to two-mile in 1898 and 1899. While he raced on roads as well, Taylor excelled on the velodrome tracks that once existed across the country. Hailed in newspapers as the “Black Cyclone,” Taylor entered the history books as the first Black American to become a cycling world champion when he won the sprint event at the 1899 World Track Championships. He then traveled around the nation and world to race against and beat the world’s best riders in the early 1900s.

Many books have been written about Taylor, who despite his athletic achievements, remains unknown to many. The authors of “Major Taylor: The Inspiring Story of a Black Cyclist and the Men Who Helped Him Achieve Worldwide Fame,” called him “the fastest man in America and a champion who prevailed over unspeakable cruelty.”

In 1928, Taylor published an autobiography whose title, “The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World: The Story of a Colored Boy’s Indomitable Courage and Success Against Great Odds.” In the book, Taylor wrote that he had no other Black athletes to offer him advice and “therefore had to blaze my own trail.”

Taylor had to cope with overt racism and prejudice throughout his life and cycling career. Some track owners banned him from competing at their venues, and Taylor was sometimes jeered and heckled by white spectators. He was banned from joining some white cycling clubs. Worse yet, he often complained of being elbowed and physically hit by competitors in an effort to block or slow him down, and at other times he was physically attacked, had nails thrown in front of his tires, and received death threats.

Born in 1878 in Indianapolis, Indiana, Taylor retired in 1910 at age 32. In his autobiography, he cited the mental strain of battling racism in competitive cycling as one reason for his retirement. Despite his racing success and countless achievements, he was forced into poverty in his later years and died of a heart attack in 1932 in Chicago.